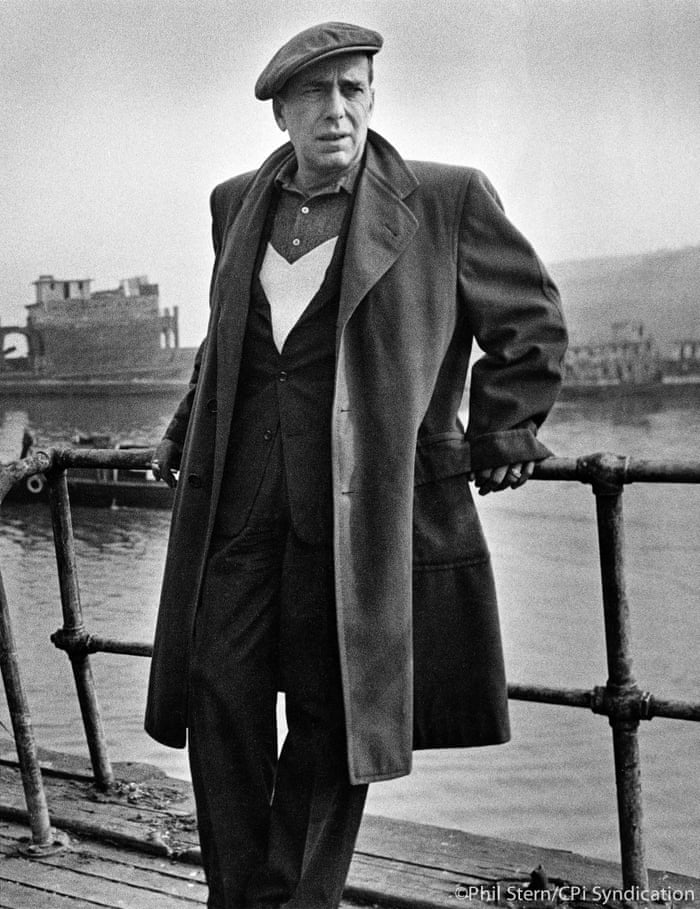

“There is no such thing as the perfect picture. That’s the challenge of photography. I was always striving for perfection, even though I knew I could never achieve it. But it kept me reaching for something.” – Phil “Snapdragon” Stern

Philip “Snapdragon” Stern was an American photographer born in 1919. He was known for his iconic portraits of Hollywood stars, as well as his war photography while serving as a U.S. Army Ranger with “Darby’s Rangers” during the North African and Italian campaigns in World War II.

Born in Philadelphia to Russian Jewish immigrants, Alix and May, Stern was later to reference Arthur Miller in describing his father as “a salesman, a la Willy Loman. I wanted to find the best way to avoid becoming my father.” The family went to live in the Bronx when Stern was 11, and he left school at the age of 16, preferring to experiment with a Kodak camera his mother had won in a free promotion. He took a job sweeping up at a Canal Street photo studio and soon acquired the skills necessary to supply “a readership that required a certain kind of picture” for the pulp Police Gazette.

At the age of 19 he completed his first reportage assignment on Kentucky coal miners for a new weekly. When Friday magazine opened a West Coast office, Stern moved to Los Angeles and started his stellar Hollywood career with a feature on Orson Welles shooting Citizen Kane. In 1941 Stern had his first spread in Life magazine, to which he contributed as long as it lasted.

In the years leading up to World War II, he was a working photographer with several magazine covers to his name and had also been a set photographer on Orson Welles Citizen Kane. When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbour he was sent to London as a US Signal Corps photographer.

He soon grew tired of snapping pictures of two-star generals, working in the dark room and attending high society events. Where was the war, the excitement, shellfire, Nazis, and combat scenes that he joined the army to photograph? His spirits were low until he read about an elite American unit forming in Scotland asking for volunteers. He quickly jumped on a train and made his way to Scotland to join the Rangers.

As a combat photographer in the second world war, he won a Purple Heart for his courage and willingness to risk his life picturing infantrymen under fire. Stern documented US troops advancing through north Africa, and was invalided home with severe shrapnel wounds to his arms and neck. In 1943 he returned to cover the Allied invasion of Sicily for Stars and Stripes, the US army magazine. According to his biographer, the journalist Herbert Mitgang: “His pictures of the invasion and its aftermath remain among the most outstanding documents in the annals of combat photography in any war, before or since.”

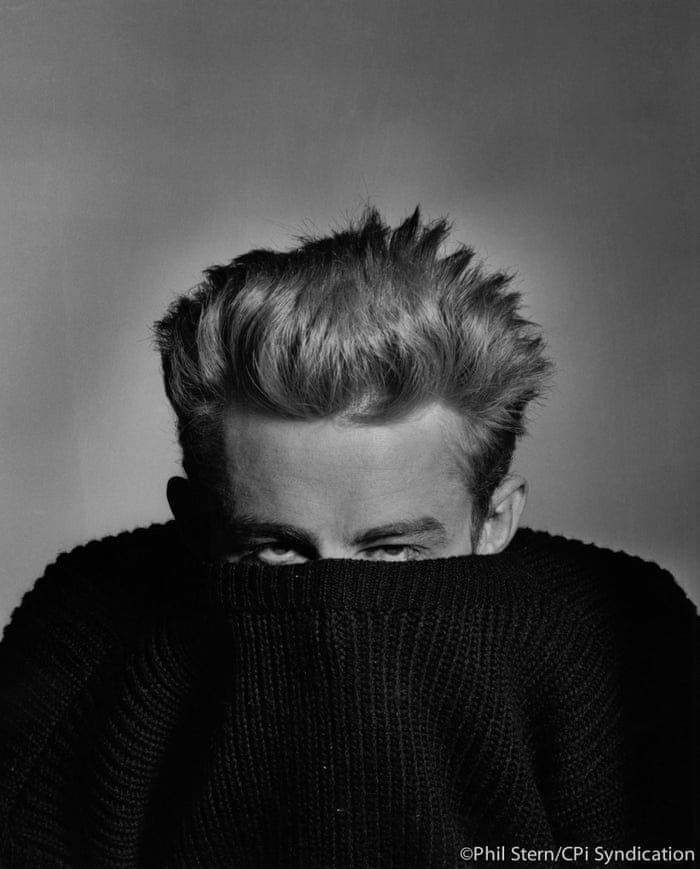

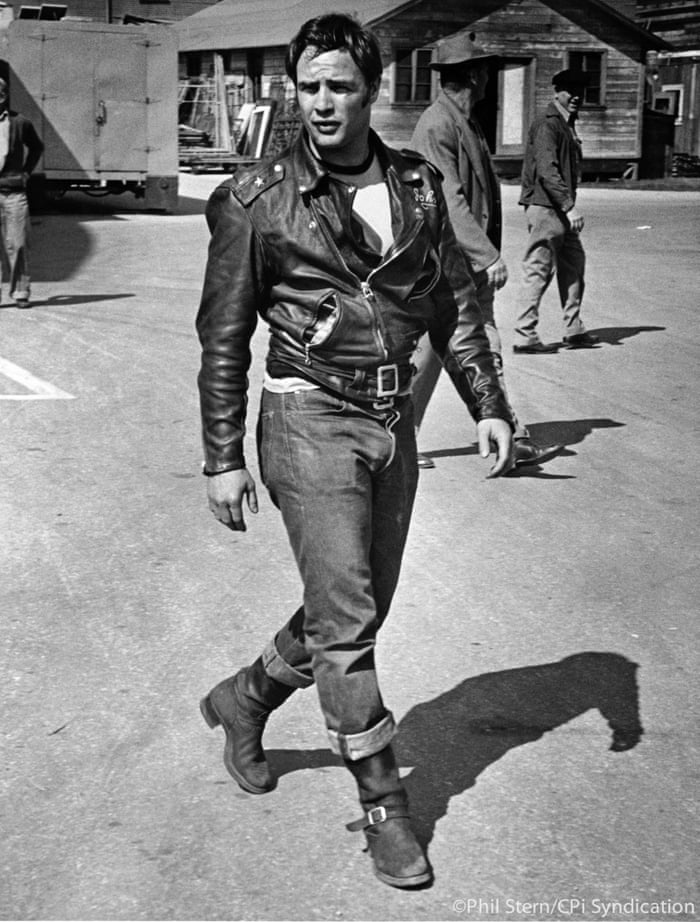

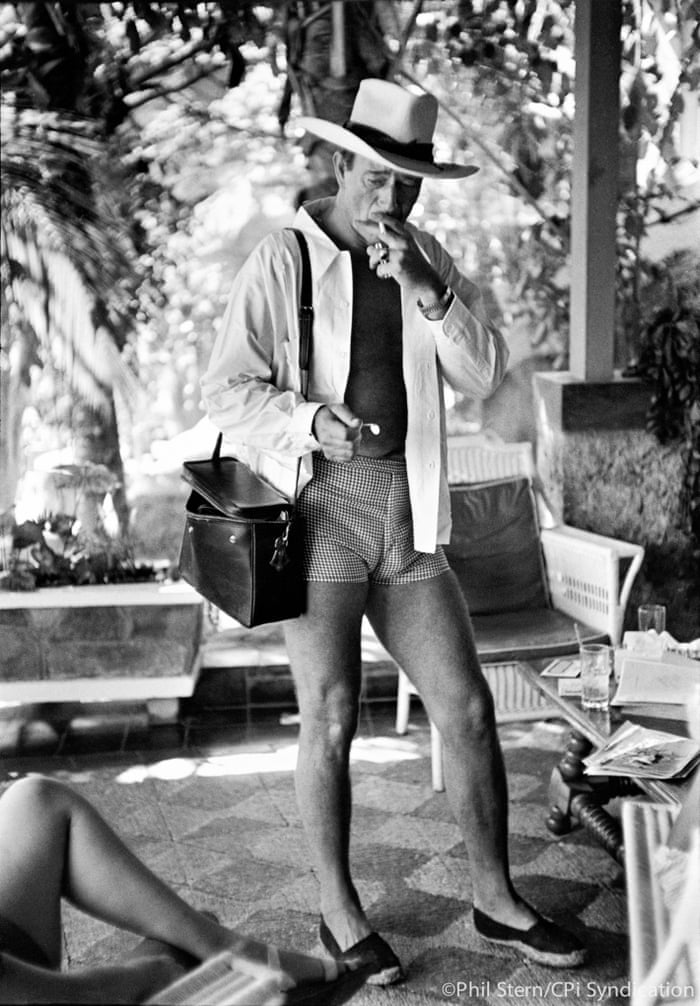

The postwar decades saw a media boom: the heyday of photo-magazines and blockbuster movies aimed at a predominantly young mass audience. Stern rode the publicity of a new generation of stars who became, at least in part through his attention, poster pinups. Interviewed later by the Los Angeles Times, he mused on his transfer from war to celebrity photography. “ [The war] very well might have helped me get access … I don’t really know for sure, because some of them wanted publicity so bad that you didn’t have to have a Purple Heart for that. All you had to have was an expensive camera.”

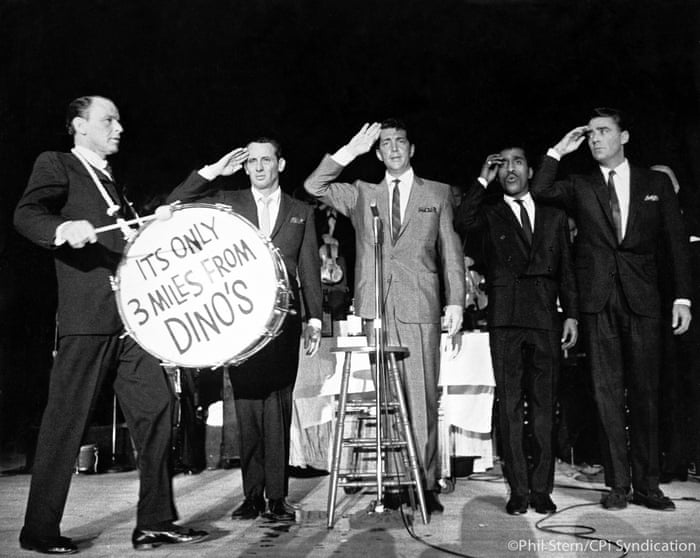

Stern’s connections enabled him to work as a stills cameraman on more than 200 films, including Guys and Dolls, and Close Encounters of the Third Kind; to contribute pictures to hundreds of book and record covers, including those for albums by Sinatra, Armstrong and Fitzgerald; and to touch on the world of politics. When Sinatra assumed responsibility for President John F Kennedy’s inaugural gala in 1960, Stern paused in shooting stills for The Devil at 4 O’Clock to deposit a note in his dressing room. It read: “Read the news today. I hereby apply for the job of resident paparazzo on your inaugural project.” It worked, and Sinatra hired Stern for the inaugural ball. His shot of Sinatra deferentially lighting Kennedy’s cigarette in a swath of smoke went around the world.

Stern was ever careful not to get too close to the stars he befriended. In his heyday he acknowledged: “Someone who knows the scene might say I was part of the gang in that I was acceptable to them, but that’s the extent of it. I was not on their A-list, but from time to time I’d be invited. Technically I was one of them for an hour and a half.”

Stern lived most of his life in a modest bungalow near the Paramount studios, cluttered with decades’ worth of photographic prints, contact sheets and negatives. In 2001, he donated his library to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. When asked what made a good picture, he gave a puzzled answer: “I wish I knew. I could keep taking more.”

A lifelong smoker, Stern died at the age of 95 in Los Angeles from COPD and congestive heart failure which he had been battling for over three and a half decades.

Fascinating. Did you spot that we had Linda Chen also Hollywood photographer on the programme although a different generation Hope all well D david kessel dokessel@gmail.com

>